Economic Outlook | Growing with GDP ... or Not

- Published: November 23, 2015, By Robert C. Fry Jr., Ph.D.

There are two main reasons why gross domestic product might not be a good benchmark for your company’s volume growth.

This is the time of year when many companies put together their plans for next year (which makes it a good time to bring in an economist to talk to your leadership team). The planning process often starts with a set of assumptions about economic growth that includes forecasts for growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) in the countries or regions in which a company operates. A company might assume, as a first approximation, that demand for its products (and sales volume if market share is stable) grows with real GDP. However, for most companies, other economic indicators are much better gauges of volume growth than is real GDP. (Since price changes are removed in the calculation of real (i.e., constant-dollar) GDP, it is never appropriate to compare growth in real GDP to growth in revenue or earnings. Revenue and earnings should be compared to nominal (i.e., current-dollar) GDP, which includes price changes.)

This is the time of year when many companies put together their plans for next year (which makes it a good time to bring in an economist to talk to your leadership team). The planning process often starts with a set of assumptions about economic growth that includes forecasts for growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) in the countries or regions in which a company operates. A company might assume, as a first approximation, that demand for its products (and sales volume if market share is stable) grows with real GDP. However, for most companies, other economic indicators are much better gauges of volume growth than is real GDP. (Since price changes are removed in the calculation of real (i.e., constant-dollar) GDP, it is never appropriate to compare growth in real GDP to growth in revenue or earnings. Revenue and earnings should be compared to nominal (i.e., current-dollar) GDP, which includes price changes.)

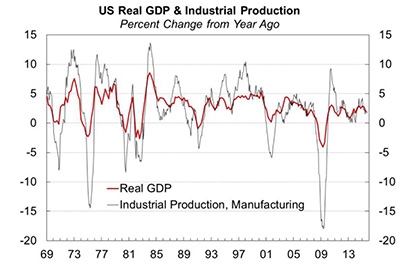

There are two main reasons why real GDP might not be a good benchmark for an individual company’s volume growth. First, some parts of the economy are more cyclical than the economy as a whole. In a good year, when GDP growth is above trend, these companies grow faster than GDP, even if the long-term growth rate is the same as for GDP. (That’s a big “if,” as we’ll discuss in the next paragraph.) But in a bad year, with GDP growth below trend, these companies grow slower than GDP. Because of what economists call the “inventory bullwhip effect,” cyclical swings get bigger the further up the supply chain you get. Thus, for materials suppliers, growth rates can fluctuate widely around the long-term trend. Only in an “average” year, when growth is near its long-term trend, will growth be close to GDP growth.

Second, few companies serve the entire economy. While there are exceptions, most companies sell either goods or services. For a materials supplier, growth in the service sector isn’t very relevant. What matters is growth in the goods-producing sectors of the economy: agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and mining. Unfortunately for US manufacturers, these sectors grow less rapidly than GDP over time. In other words, the service share of GDP tends to grow over time. This is basically true for all developed economies. At the earliest stages of development, most economies are primarily agricultural (defining agriculture broadly to include forestry and fisheries). As growth “takes off,” manufacturing grows faster than GDP, so that the manufacturing share of GDP grows while the agriculture share shrinks. (Construction, mining, and utilities tend to grow with manufacturing, and the World Bank lumps those four sectors into one “industrial” sector for data purposes.) As economies mature and material needs are met, growth in the service sector eclipses growth in the manufacturing sector, and the service share of GDP grows while the manufacturing share shrinks. In the US, the manufacturing share of GDP has trended down since 1969, with small increases during economic expansions failing to offset large declines during recessions.

Most of the world has now reached the stage of development where the manufacturing sector (and the industrial sector more broadly) grows less rapidly than GDP, while the service sector grows more rapidly. Data from the World Bank show that from 2000 to 2014, Switzerland was the only country among the developed countries of Western Europe, North America, and Japan where the manufacturing share of GDP grew. Aside from South Korea, Hungary, and Poland, all of the countries with rising manufacturing shares were poor countries in Eastern Europe, Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Notably, China has already reached the point the manufacturing share of GDP has started shrinking, and this shift is accelerating as China makes the transition to consumer-led growth.

For most materials suppliers, industrial production is a better gauge of volume growth than is real GDP. In the US, total industrial production includes the output of the manufacturing, mining, and utilities sectors. Some countries also include construction. I tend to focus on industrial production in manufacturing, for a couple of reasons. First, most of the businesses that I’ve worked with over the years have sold most of their output to other manufacturers. Second, output of utilities is often driven by weather. Severe weather, which boosts demand for heating in the winter and air conditioning in the summer, lifts industrial production, making something that is bad for an economy look good in the data. From 1969 to 2000, industrial production in US manufacturing grew at the same 3.2% rate as real GDP. Since then, however, industrial production in manufacturing has grown at just a 0.4% rate, much less than the 1.7% growth rate for real GDP. And if you’re not selling into the high-tech communications and electronics sector, even this 0.4% growth rate overstates growth in demand. Industrial production for manufacturing ex high-tech, my favorite measure of “old-economy” manufacturing in the US, has actually declined since 2000. Manufacturing outperformed GDP early in the recovery, but the outperformance has ended as the dollar has strengthened.

It might be tempting to use industrial production indexes for the specific industries your company sells into, but be careful. Data for individual industries are subject to extremely large revisions for several years after their initial release. While historical data might fit your sales volume very well, recent data (and forecasts based on them) might give a very misleading picture of the market conditions you are facing. It’s generally better to use a broad industrial production index, which is subject to much smaller revisions, rather than the index for an individual industry. For some industries, however, there are better measures than industrial production. Data are available for motor vehicles sales and production in most of the world. Many countries publish data on new construction, although there is little standardization across countries. (Some publish housing starts or building permits in units; others in square meters.) Consultants in the electronics industries publish data on computer and mobile phone sales and on semiconductors and semiconductor equipment. If you sell into any of these industries, you should use these data.

I once heard a senior executive dismiss a particular business as unimportant because “it just grows with GDP.” But as long as new businesses are being formed, existing businesses, in total, must grow less rapidly than GDP. Thus, the business that the executive was dismissing was, by definition, above average, and that executive’s company would be doing much better if it had more businesses that grew with GDP. Unless they are focused on countries at the lowest stages of development, most materials suppliers should not expect organic volume growth (growth not attributable to acquisitions) to keep up with real GDP over the long run, although they might briefly grow faster during the best years of the economic cycle. And because goods prices fall relative to service prices over the long run, the shortfall is even larger when you compare revenue or earnings with nominal GDP.

Robert Fry is chief economist of Robert Fry Economics LLC, where he analyzes the global economy to help decision-makers at manufacturing companies and wealth management firms. He publishes the Current Economic Conditions newsletter and is a regular guest on the "Money & Politics in Delaware" radio show. Until retiring in June 2015, Robert was senior economist at DuPont. While there, Robert and his colleague, Bob Shrouds, were named among the top economic forecasters by Bloomberg, USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal. In 2005, they won the prestigious Lawrence R. Klein Award for Blue Chip Forecasting Accuracy. While at DuPont, Robert gave more than 800 speeches on the economy to DuPont management, business teams, customers, and trade associations. Robert received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Ohio University and his master’s degree and PhD in Economics from Harvard University. To receive Current Economic Conditions every month or to book Robert to speak to your company's leadership or customer/supplier event, please contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Copyright ©2015 Robert Fry Economics LLC. All rights reserved. Distribution, reproduction or copying of this copyrighted work without express written permission of Robert Fry Economics LLC is prohibited.