Economic Outlook | US Manufacturing: Dispersed Gains, Concentrated Losses

- Published: February 29, 2016, By Robert C. Fry Jr., Ph.D.

The biggest risk to US manufacturing and the economy as a whole is that corporate management overreacts to declining stock prices or weak nominal earnings growth by cutting investments (or employees) that are necessary for long-term growth.

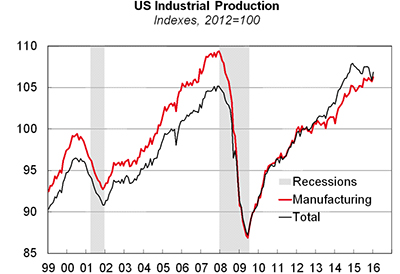

Industrial production in US manufacturing rose 0.5% in January, taking it to a new post-recession high. The increase should quiet talk of a “manufacturing recession,” although it might not convince those who focus on total industrial production rather than production in manufacturing. (Total industrial production rose 0.9% in January because of a jump in utility output caused by cold weather, but was still down 1.2% year-over-year.)

Industrial production in US manufacturing rose 0.5% in January, taking it to a new post-recession high. The increase should quiet talk of a “manufacturing recession,” although it might not convince those who focus on total industrial production rather than production in manufacturing. (Total industrial production rose 0.9% in January because of a jump in utility output caused by cold weather, but was still down 1.2% year-over-year.)

Even if manufacturing hadn’t jumped in January, the recent small declines would have lacked the depth, duration, and the dispersion to qualify as a recession. In particular, recent weakness in manufacturing has not been widely dispersed; it has been concentrated in a few industries. Industrial production has continued to trend up, albeit very slowly, in most manufacturing industries.

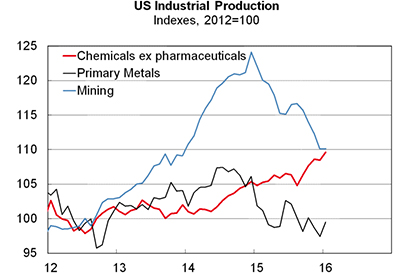

Of the 20 manufacturing industries for which the Federal Reserve reports industrial production, only five posted year-over-year declines in industrial production in January. Three of these—primary metals (-2.3%), fabricated metal products (-2.0%), and machinery (-4.1%)—have been hit hard by the decline in demand for well piping and oilfield machinery associated with decline in drilling activity caused by the collapse in oil prices. They’ve also been hurt by competition from abroad, as a strong dollar and surplus capacity, especially in China, have reduced the price of imports.

The other two manufacturing industries that posted year-over-year declines in January—apparel & leather goods (-9.2%) and paper (-2.7%)—have been trending downward for years; the recent declines do not indicate a cyclical downturn. Industrial production in mining was flat in January, but was down 9.8% year-over-year and is likely to fall much further.

The other 15 manufacturing industries posted year-over-year increases in industrial production in January. Most increases were small, but wood products, nonmetallic mineral products, electrical equipment & appliances, and motor vehicles & parts were all up by 4% or more. Total chemical industry production was up just 2.9%, but chemical production excluding pharmaceuticals hit a post-recession high in January and was up 4.6% year-over-year. Production of wood products, nonmetallic mineral products (e.g., stone, clay, glass, cement), and appliances is being boosted by the slow but continuing recovery in housing.

While housing starts fell sharply in January due to bad weather, housing permits, a better measure that is less affected by weather, fell just slightly. The three-month moving average in single-family housing permits hit an 8-year high in January, suggesting that the housing recovery will continue.

Industrial production in the chemical industry is being boosted by new capacity built to take advantage of the abundance of cheap natural gas liquids associated with the shale gas boom. With the planned expansion in capacity still in its early stages, industrial production of chemicals (and the plastic and rubber products that use chemicals as a raw material) is likely to continue to grow for several years.

Those who continue to recite the “manufacturing recession” mantra point out that the Institute of Supply Management’s composite PMI (purchasing managers’ index) for manufacturing was below 50, indicating contraction, for a fourth straight month in January. However, the production index, which gauges current output, never fell below 49.8 and was back above 50 in January. The new orders index, which leads industrial production, rose from 48.8 in December to 51.5 in January.

I am not saying that US manufacturing is strong. Outside of the few industries that are benefitting from the recovery in housing or the shale-gas boom, it is basically stagnant, as the boost to US consumer demand from lower oil prices has been offset by reduced drilling, a strong dollar, weakness abroad, and (recently) a slowdown in inventory accumulation. Furthermore, my leading indicators are more consistent with a small near-term decline than with a resumption of growth. But it is irresponsible to prematurely throw around terms like “manufacturing recession” or “industrial recession” to boost your TV ratings or your newsletter circulation, not just because such terms are wrong, but because they can cause consumers, investors, and businesses to take actions that trigger a recession.

So far, there’s no evidence that talk of a manufacturing recession or declines in stock prices (through February 11) have spread to consumer spending. Retail sales rose 0.2% in January, and December’s 0.1% decline was revised up to a 0.2% increase. With retail prices declining, these small nominal increases are consistent with solid real growth. Retail sales excluding autos, gasoline, and building materials—the so-called “control group” that goes into the calculation of Gross Domestic Product— rose 0.6% in January and were up 3.6% year-over-year.

Light vehicles sold at a 17.5 million seasonally adjusted annual rate in January. The selling rate likely hit a monthly peak during the September–November period, but remains very strong and is likely to set another annual record this year. Real GDP grew at just a 0.7% annual rate in the fourth quarter, but is likely to grow at a 2%–3% annual rate in the current quarter.

Industrial production indexes by country show a similar pattern to indexes within US manufacturing: a few countries (most notably Brazil) showing large declines, a few (including Spain and much of Central Europe) showing strong growth, and most (including the Eurozone as a whole and Japan) clustered around the flat line. China is not growing as fast as the “official” 5.9% year-over-year growth rate for Value Added of Industry indicates, but my own index for China suggests that Chinese manufacturing is growing again. Market manufacturing PMIs remain in the 52-53 range, consistent with slow growth, in the United States, Mexico, Japan, and the Eurozone, but remain below 50 in China, Brazil, and Russia.

Some analysts interpret recent declines in global stock prices as evidence of a cyclical contraction in economic activity, i.e., a recession. I see them as evidence that investors are realizing that their expectations of earnings growth, which should be linked to their expectations of long-term economic growth and inflation, have not been realistic and need to be adjusted downward. The biggest risk to US manufacturing and the economy as a whole is that corporate management overreacts to declining stock prices or weak nominal earnings growth by cutting investments (or employees) that are necessary for long-term growth. When weakness in earnings growth is due to a general lack of inflation rather than to declining volumes, the most logical response is to adjust your earnings expectations, not your investment and employment.

US investment in plant and equipment declined in the fourth quarter, but the decline in oil drilling accounts for most or all of that decline. Unless companies outside of the petroleum industry panic and cut investment broadly, moderate growth is likely to continue.

Robert Fry is chief economist of Robert Fry Economics LLC, where he analyzes the global economy to help decision-makers at manufacturing companies and wealth management firms. He publishes the Current Economic Conditions newsletter and is a regular guest on the "Money & Politics in Delaware" radio show. Until retiring in June 2015, Robert was senior economist at DuPont. While there, Robert and his colleague, Bob Shrouds, were named among the top economic forecasters by Bloomberg, USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal. In 2005, they won the prestigious Lawrence R. Klein Award for Blue Chip Forecasting Accuracy. While at DuPont, Robert gave more than 800 speeches on the economy to DuPont management, business teams, customers, and trade associations. Robert received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Ohio University and his master’s degree and PhD in Economics from Harvard University. To receive Current Economic Conditions every month or to book Robert to speak to your company's leadership or customer/supplier event, please contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Copyright ©2015 Robert Fry Economics LLC. All rights reserved. Distribution, reproduction or copying of this copyrighted work without express written permission of Robert Fry Economics LLC is prohibited.